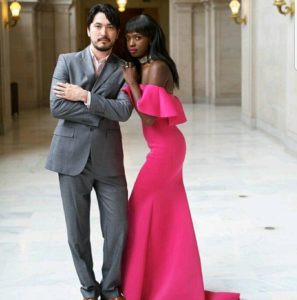

This fine Zambian gal named Adeline Chi Chi (on the right. Yes boys, she’s happily married!) is where it all began. Adeline and our family have never met in person. We were introduced thru a friend, Doc Erik. Through chance, she was from the same city in Zambia as Latitude 15 hotel. That’s how magic happened.

Upon completion of the school this week (November 2018) she wrote me this note.

Hi there!

Congratulations on the school! Audrey and Rodney have been sharing the updates with me. What a job well done. It’s difficult to get projects done this quick in Zambia! I am so happy for you, and I hope Audrey and Rodney were able to manage the project to your standards. I threatened them not to mess up. (Joking).

Thank you for your big heart. Thank you to your wife and children. Thank you for your sacrifice of time and money. I have seen so many children my dad helped who were once street boys and now they are doctors, teachers, and engineers. I remember he got Ba Mwali from the village. Everyone had given up on him. He was a non functional alcoholic, and dad saw something in him. He brought him in our home, trained him and helped him clean up. It is so life giving to see he continued on his own . I told him he is very lucky to have met you and work with you. It’s a lottery win for him. Never in a million years would he have been able to build a school like that.

You have truly inspired me. My dad’s project and school went down since his stroke. Since he was the main financial resource for everything, it became difficult to continue to run. After his stroke everything fell on my shoulders. I was the only one who could help. I managed for 5 years because I was doing very well financially and had lots of properties here but I was young and stupid and I lost everything in a bitter divorce and had to pay alimony for a year. At that point, between dad’s hospital bills, the orphanage, church, and school, it was difficult to keep up. I had to talk dad into giving everything up.

His dream is to see everything running again like it used to. He believes in the power of education. He loved helping the less fortunate. I didn’t want to do it anymore because I just wanted to build my own life back. Giving became to stressful.

Your project has revived my spirit and inspired me to resurrect my dad’s work. ❤️. Thank you.

School for 400, Where there was none.

Pilots, doctors, writers, computer techs, parents, anyone and anything can happen. Have faith in the process.

Ba Mwali is the man on the ground, the principle and local project leader along with Audrey and Rodney. Without them, the vision and hard work, this school never happens.