Xi’an Video Story Board, Research Subjects

BIG QUESTION FOR THE MONTH:

Why is the One belt, One Road Initiative of current President Xi So important to modern China? How Does it relate to the view of China by the rest of the world. And versus the United States and it’s current worldview and policies?

The Trip: Train to Xi’an

Food: Defachang resto for handmade dumplings. Can we film in the back?

Place: Wild goose pagoda 652 ad

Bike walls

Silk road source research

Bell town circle. Time square

Activity: Sang ye tang foot washing17 dollars

Ancient Islam at the Source of the Silk Road: Old city center. Muslim district pay

[60k Muslims in Xian

Ok inside of Mosque

When and how did Islam come to China

First in China by silk road

Dress ok? Only Muslim

Muslim shops]

Red lanterns

Terra Cotta Warriors

700k workers, 38 years

3rd century BC

Each worker buried inside to protect identity

1200 exposed. 6800 to go

How they are made, see the place. One month to make, price 7USD to 2000 USD (in 2008)

Watershow North square, light city walls, run across 66million bucks

Fighting stage show Ting Dynasty Theater

Basic Research Topics and background

| Xi’anyang, just north of the present day Xi’an, was the capital of the Qin empire, home of the first Emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang, and site of the fabled terracotta warriors. Chang’an (another name for Xi’an) was the home base for the Han dynasty (206 BC – 220 AD), a starting point for caravans heading west on the Silk Road, and a center of Chinese art and culture during the Tang dynasty. Visiting Xi’an with kids, plan on spending more than one day to explore this ancient capital of China. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Bell Tower and Old City Wall – During the Ming dynasty, Xi’an was defended by a substantial city wall and watchtowers. You can walk on top of ancient city wall, it’s quite flat and wide, and beautifully restored. The grassy area just outside the wall would have been a moat. In the center of the old city wall is the Bell Tower – the bell was rung to mark times of the day. Climb up the Bell Tower, a wonderful three story wooden tower with glazed tile roof, there’s an observation deck on second level. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Shaanxi History Museum – The Shaanxi History Museum is a beautiful modern museum, with tons of exquisite Chinese treasures, including paintings from Tang dynasty tombs in the area. The collection is fabulous – golden bowls and dragons, jade weapons, seals and bracelets, ceramic figures (the camels are fantastic), and don’t miss the exhibit of Tang costumes and personal ornaments. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Big Wild Goose Pagoda – In the 7th century, the Tang dynasty monk Xuan Zang took off for India, collected Buddhist texts, and returned to China, bringing the Buddhist religion with him. The Big Goose Pagoda was built to store the Buddhist scriptures, and although the Pagoda has been rebuilt over the centuries, it hasn’t significantly changed in appearance. Climb up the pagoda, winding stairs up seven levels 331 ft. high, with windows to look out at each level. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Tang Paradise (Tang Dynasty Lotus Park) – Tang Paradise is a newly opened cultural theme park that re-creates life in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907 AD). Explore Tang style buildings, listen to Tang music, watch colorful dance shows, acrobatics, and martial arts demonstrations. There are water play areas for kids, get your picture taken on the back of a two humped camel, and in the evening, watch a spectacular water show, a movie projected on water fountains in the lake. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Museum of Terra Cotta Warriors and Horses – In the Qin Shi Huang Mausoleum Site Museum, Kids will be impressed by the boggling terra cotta army, thousands of ceramic warriors and horses guarding the nearby tomb of the first emperor of China, Qin Shi Huang (Qin Shi Huangdi). A truly amazing archaeological discovery, the terra cotta warriors stand in rows in earthen tunnels, prepared for battle (pit 1 is bigger than two football fields). The expressions on the faces of the figures are so real, it’s like staring into the face of ancient China over 2000 years ago. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Spend time checking out the details of these life-size warriors, plated armor, footgear and headgear, and Mongolian horses. Pick up the audio tour for on-the-spot information. And don’t miss the smaller museum with a shiny bronze sword and two large reconstructed bronze horse chariots. |

Silk Road and Islam Primer

An ancient imperial capital and eastern departure point of the Silk Road, Xi’an (formerly Chang’an) has long been an important crossroads for people from throughout China, Central Asia, and the Middle East, and thus a hub of diverse ethnic identities and religious beliefs. The central location of Xi’an in what is now the Shaanxi Province, near the confluence of the Wei and Feng Rivers, helps explain why the area was the site of several important imperial capitals for almost a millennium of Chinese history. The first unified Chinese empire, the Qin Dynasty (221-206 BC), had its capital just north of the current city, where the impressive tomb complex of the Qin emperors was discovered, famously containing more than 8000 terracotta statues spread over some 56 square kilometres.

The Qin was succeeded by the Han Dynasty (206 BC-220 AD), who began the construction of Chang’an. It was under the Han Emperor Wu Di (141-87 BC) that the first Chinese missions were sent to south-eastern Asia, central Asia and eventually even Rome, marking the beginnings of the Silk Road. Han Emperors substantially expanded the capital city, erecting many new palaces, but the glory of Chang’an came to an end in 24 AD with the collapse of the dynasty, and after looting and destruction, it subsequently fell to the status of simply a provincial city.

Chang’an was revived as the capital city in the 4th century AD, and witnessed a cultural florescence in part thanks to the fact that it became a centre of Buddhist learning. Several important Buddhist pilgrims and translators resided there in the early 5th century, among them Faxian, who travelled to India, and the scholar Kumarajiva. Following the accession of the Sui dynasty in 581 AD, the first Sui emperor decided to move the capital, and built an entirely new city just south of the original, on the exact location of modern Xi’an.

The city continued to be the principal capital of the Empire and entered the greatest period of its development under the Tang Dynasty (618-904), occupying some 84 square kilometres, with around one million inhabitants. The Tang period was noteworthy for the impact of Western products and fashions on Chinese elite culture, and the teeming markets of the capital played a significant role in the dissemination of such goods. Among the dominant figures in this era were Sogdian merchants from the region of Central Asia which encompasses today’s Samarkand, who were vital agents in the transporting and trading of goods to China.

Under the Tang, the city was also a major religious centre, not only for Buddhism and Taoism but also for several religions which were relatively recent arrivals in China: Zoroastrianism, Nestorianism and Manichaeism. The most famous of all the Buddhist pilgrims, Xuanzang, brought copies of the Indian scriptures to the city, which he then translated. One of the few major Tang-era buildings left in Xi’an today is the Big Wild Goose (Dayan) Pagoda, first built in 652 AD, housing the library that Xuanzang collected. The current structure was re-built in 701-704; by climbing to its seventh story, which “rubs the blue sky’s vault,” a Tang poet Cen Shen felt he was able to “bypass the world’s bounds”.

The Japanese pilgrim Enin was in Chang’an in 840 and noted that there were monks from the “Western Lands” (apparently India) in one of the several hundred monasteries there, who still did not know Chinese very well but presumably were helping with the interpretation of Sanskrit versions of the Buddhist texts. He later described South Indian, North Indian, Ceylonese, Kuchean (Kucha in the Tarim Basin), Korean and Japanese monks among the foreigners in the city. He goes on to note that there were four teeth of the Buddha in the city, three of them having come respectively from India, Khotan and Tibet and the fourth from heaven.

The spread of religions other than Buddhism under the Tang Dynasty can be documented fairly specifically. A stele (an inscribed stone pillar) erected in 781 relates the introduction of Nestorian Christianity as early as 635 AD by Syrian priests. The text and carvings exhibit a syncretism of Christian and Chinese traditions. Zoroastrianism received some impetus when the last of the Sassanian (Iranian) princes Firuz took refuge in China in the 670s, having fled the Arab invasions. Manichaeism also was connected with the arrival of Persians at the Tang court as early as 694 AD.

However this atmosphere of tolerance and religious pluralism broke down in the 9thcentury, and disorder and looting accompanied the last years of the Tang Dynasty, as its power weakened in the capital. With the collapse of the Tang at the beginning of the 10thcentury, Chang’an decayed rapidly. However, it continued to play a role in Western trade and experienced a revival under the Ming, beginning in the late 14th century.

Undoubtedly it was in the Ming period that the large Muslim community in Chang’an really took root and its members became largely Sinicized. Muslim merchants arrived in China much earlier both by sea through the ports of the South China coast and from Central Asia, but their full integration into Chinese society came later. Although first built in 742, the architecture visible today in Chang’an’s Great Mosque (the Qingzhen Dasi) dates from the late Ming period, for example, its entrance gate was erected in 1600-1629. In its arrangement of courtyards and purely Chinese-style architecture, the mosque is visual evidence of the degree to which there was a syncretism of Islam and Chinese culture. The inscription on the “One God Pavilion” is the Muslim declaration of faith “God is One” rendered in Chinese characters. The mosque as we see it today is located in a Muslim quarter of Xi’an, not far from the location of the western market whose merchants played an important role in the continuing trade with the West throughout the Ming and Qing dynasties, along with the Silk Roads to Inner Asia.

China! Has a unique color and power, a BEAST all it’s own.

China! Has a unique color and power, a BEAST all it’s own.

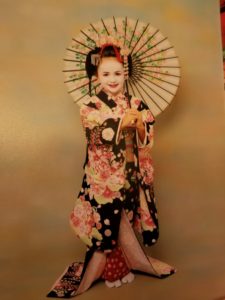

Growing up with only brothers, I’m not quite sure what exactly is the definition of “a little girls best day ever”, but I suspect heading out in Kyoto with Maman to get kitted up in full makeup as Geisha is pretty darn close.

Growing up with only brothers, I’m not quite sure what exactly is the definition of “a little girls best day ever”, but I suspect heading out in Kyoto with Maman to get kitted up in full makeup as Geisha is pretty darn close.